ARTIST / Artist

BEVERLY FISHMAN

BEVERLY FISHMAN

Beverly Fishman creates powerful abstract paintings that address technology and the pharmaceutical industry. Fishman lives and works in Detroit, where she teaches painting at the Cranbrook Academy of Art.

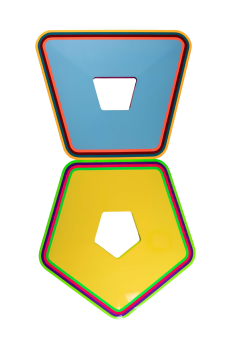

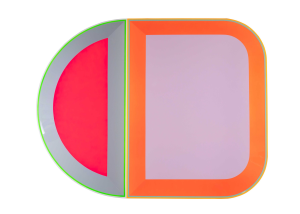

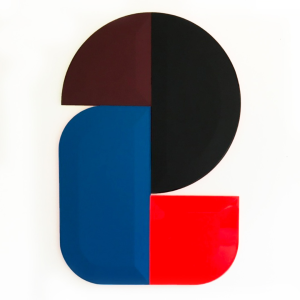

Fishman is a painter with the concerns of a sculptor, making paintings that require high levels of production. Her studio practice includes manufacturing uniquely shaped supports and consulting with automotive paint specialists to get the background she needs to achieve industrial finishes.

Her work synthesizes form, color and social content in dialogue with tradition. Although they seem to have a formalist abstraction, they exude representation and have very direct references to the body and the world.

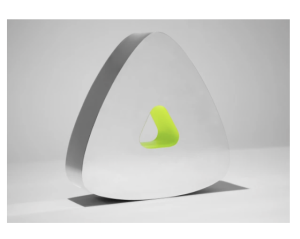

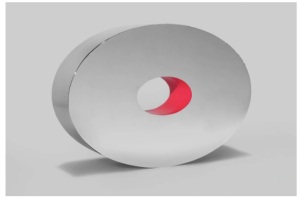

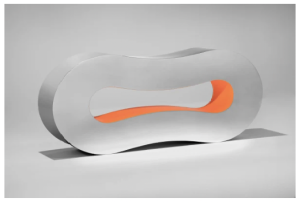

Her current wall reliefs are painted with urethane paint and are appropriated from actual pills that she finds images online. The cuts in their surfaces correspond to the score marks that allow these drugs to be divided into smaller doses. Thus, although they look abstract, her paintings are tied to problems like attention-deficit disorder, opioid addiction, anxiety, and depression. Their forms connect them to the social problems of today.

Fishman starts by researching shapes online, them makes a series of collages exploring different color combinations using a wide range of materials. She uses paint sample cards acquired from home supply stores, color swatches, and fragments of vinyl signs to create mixtures of different color systems, both natural and synthetic, which are then realized in automotive paint. While the forms evoke pills, many of the colors refer to skin tones, either with fleshy hues or with pigmentation associated with makeup. Once she has chosen the final palette, she then has the tablet shape fabricated in wood and painted by specialists. Once the work is back to her studio, she continues to alter them until they finally surprise her.

Beverly Fishman belongs to a generation of painters that needed to make the connection between abstract form and external reference more explicit than before—by incorporating texts and diagrams, for example, or by working with simple icons that looked like things in the world.

Fishman’s work can be associated with Ross Bleckner’s in the sense that, for years they have shared an interest in the form of the biological cell as a signifier of identity and disease. And just like Peter Halley, she has worked with abstract forms that she does not view as abstract. Just as Halley saw squares as referring to cells and prisons, she sees very simple geometric forms as—in part—representations of social issues surrounding the use and abuse of certain drugs. If she is asked to name artists with whom she feels in dialogue she cites: Anne Truitt, Judy Pfaff, Elizabeth Murray, Nicholas Krushenick and Ellsworth Kelly.

For Fishman, it is important that the viewer know the content of her work. Her titles are significant, because they help to direct people’s readings. On the other hand, even if a viewer comes to her paintings without knowing the concepts behind them, she believes that there is enough in the works themselves for the spectator to get that they are far from pure. The sleek industrial jobs, the sometimes-sickly saturation of hues, the jarring contrasts of natural and synthetic colors—these are qualities that, for Fishman, push the paintings in the direction of a critique of geometric abstraction, with its traditional connotations of transcendent aloofness and apartness from life.

In her work, she hopes, the colors and forms—even if you know nothing about them—evoke a technologically mediated world, one in which our desires are fed by the mass media and our identities are influenced by the products that we consume.

–